The storied history of co-operation

As you may have seen in the piece about the early ISP market, the atmosphere of tense competition in the early days made it very unusual to have any kind of co-operation. That was a pity in many ways.Unlike the pities that the early ISPs had for each other, which were roughly the size of the world’s smallest violin. One of the largest unfortunate facts was the unintuitive-to-outsiders but completely true situation that each ISP had concentrated on getting their own connection to the outside world, but not to each other. Just to spell it out, that meant that any email/web connection/etc that went from, say, one Irish company to another, literally went across to the U.K., bounced around a few routers there, and then came back. That is, of course, if it didn’t go to the USA and back instead!

Just on an intuitive basis, the problems with having to go to the US if you want to talk to your neighbour are pretty clear: it takes longer, it costs more, and it’s using congested continental links to do something that should ideally be taken care of by a piece of cable strung between your houses. In other words, bandwidth gets spent on Ireland-to-Ireland communication that should have been spent on Ireland-USA communication.

Which is actually, as best I can tell, how the first inter-provider connection happened in Ireland. PostGEM and Ireland On-Line happened to have cabinets next to each other, so one day, Ronan Mulally of IOL enterprisingly strung a cable between the two of them and hooked them together: boom, vastly decreased time to cross-communicate, vastly improved bandwidth, and lowered costs for both participants. That – the cost angle – probably explains why the rest of the community shrieked like a wobbly modem when they found out.

So the mood of the industry shifted from trying to beat each other on the quality of their way of getting out of the island,Resonances with immigration only partially intended. into cost-saving when going inside the island. A number of people put together a rough proposal to put equipment in one place and the (unfortunately utterly doomed, but they weren’t to know that) negotiations for the DINX, the Dublin Internet Exchange began.

Background

So it turns out that this pattern, of organisations getting together to end the absurd pattern of being unable to talk to each other well, is not particularly new.Those of you alive in the last century will recall that the country’s two GSM operators were unable to send SMSes to each other for years, finally being fixed by agreement in mid-1999. It might have particular resonance in Ireland, because proportionally more of the world lies offshore, but it’s not new to the world. Indeed, for those of you who are interested, the economics and history of exchange points in general are explained in great detail in many places, such as the IXP Interconnection Library - look at publications by Bill Woodcock in particular.

But for our purposes, we just need to mention a few key points. In a local market, it makes sense for almost everyone to get together and agree to send traffic to each other for free. This is called peering, I suspect because it renders the organisations who exchange traffic, well, peers. There are exceptions, of course: indeed, important ones. There are those sets of organisations who either have content your users would like to see (known as content networks) or users that the content networks would like to access (known, endearingly, as eyeball networks.) Those whom you would pay to access, because you want their stuff, should not peer with you, economically speaking. Many exchanges work around these different motivations by mandating that any organisation who joins has to peer with a number of other firms at the exchange: they can’t just turn up and file their fingernails, electronically speaking.

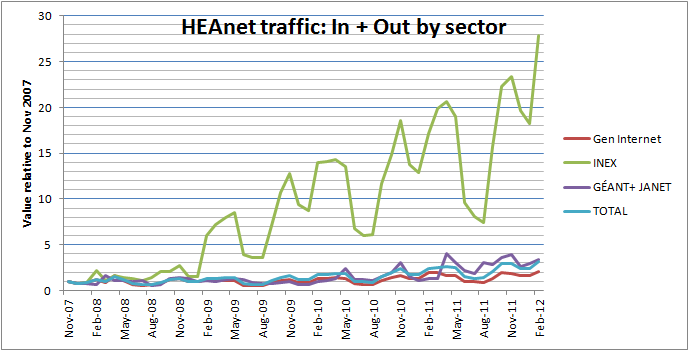

Let me make the point graphically about how valuable local peering can be by including the HEAnet traffic graph from 2007 to 2012. HEAnet are, it is true, perhaps a bit of an exception in that they have a highly local focus, but the following graph should show you what is potentially at stake:

Forty DINX and fifty packets

So Mike Norris, deeply influential and always community minded, put together a proposal to start an exchange in Ireland in 1995. At that stage, it was basically Eircom, IEunet, HEAnet, PostGEM, and IOL. The proposal very much took the lines of the LINX, the world-famous London Internet Exchange, with help from the then CEO Keith Mitchell. Matters proceeded to the tender stage, but the proposal floundered essentially because it was just that shade too early: unlike today, there simply wasn’t that much datacentre space around, and the space that was available was very costly.

The DINX ended up in a situation where the cheapest tender response was ten times cheaper than the next least costly option. Unfortunately, the cheapest response was from one of the proposed members. So the DINX could either be neutral and too dear to start, or be thoroughly partisan, and cheap enough to actually start. Unsurprisingly, that effort failed when the putative members were unable to come to agreement. You might think that’s making a very big deal of the property of neutrality when such substantial costs were at stake, and yes, you’d be right – but done for good reason.

First of all, all the other European exchanges at the time were seen to be successful as a result of their neutrality, not despite it – in other words, those exchanges could make decisions in favour of the broadest mass of their members, even if happened to inconvenience one of them, which at a time when incumbent telecoms when more powerful than they are today was really useful. (It’s still useful today.) Secondly, any member who happened to, say, own the place that the hosting was provided in could exert some financial or process-based leverage at a later date – perhaps when they’d been taken over by a different company. Finally, lobbying government on mutually beneficial issues can be done very effectively by a neutral representative body, and is taken substantially less seriously when it’s just (say) Esat complaining again.Note: I say European exchanges above. The American market was different, and had successful non-neutral commerical offerings from early on. A lack of available money, less competition, and a more homogenous regulatory and business-friendly environment probably contributed to that.

That failure aside, it wasn’t long before the market matured enough to provide a reasonable cost for this potential operation. Taking a leaf from the same book that gave us the Windscale to Sellafield transition, the new exchange effort was named INEX, for Irish Neutral Exchange, putting neutrality at the heart of what it was about. The successful responder was CARA, close to Fenian Street near the Alexander Hotel, and the oh-so-very-small installation of equipment required to get the four founder members passing data to each other.It was a 10 meg ethernet hub, which these days wouldn’t even have enough bandwidth to tie a shoelace. Personally verified by Anna from HEAnet.

We’ll have a CARAnary

As you might expect, such an ISP/telco-heavy initial membership, combined with “delicate sensibilites” with respect to a sparse market, led to a number of effects. First, the exchange was very stable, because it didn’t change very much: it didn’t adopt many new services, and only gradually acquired additional customers. This was partially by design, unfortunately – to quote the INEX development plan from 2003, there were “early requirements that prospective members needed to be full ISPs with independent transit and not be connected to an existing member.”

You might have a hard time seeing this as anything other than protectionist, and you might well be right. Certainly it’s major effect was to prevent organisations who didn’t have their own international connectivity from joining, which was short-sighted, since supposing everyone who could join did, it would cause any member’s INEX bandwidth to be used up much more quickly. So the net effect (pardon the pun) was to slow the potential growth of the exchange, at the cost of increasing the total costs for new entrants. I recall that rule causing upset on at least two occasions, once when a company from the West who shall remain nameless offered to meet ISP-consultant-me and, slightly foaming at the mouth, referred to INEX members as a golden circle.For old-timers, not so much a golden circle… more a sort of token ring. I rather got the impression he didn’t like it. The other time was when an INEX member was presenting in front of an international audience about INEX, and the protectionist character of the clause was called out for substantial negative comment by an extremely influential senior member of the networking community.Oh, all right, Randy Bush, if you must know. It was deeply uncomfortable.The clause was really written for a particular era, and quickly outlived its usefulness. Once serious content hosting companies came along, there was clearly a need to change: a content hosting company has websites that the rest of the INEX members want to access, but a) doesn’t necessarily have its own international bandwidth and b) shouldn’t go “behind” one of the members, because then bandwidth is used less efficiently. (Thankfully, it was changed in the period running up to the INEX Development Plan of 2002/2003.)

The original directors on the B10 form were the staff of Colm Watter’s company, because they were involved in the setup. At that stage, it was common practice to buy a pre-formed company and change the directors afterwards. In INEX’s case, it was Mike Norris (HEAnet), Barry Flanagan (Ireland On-Line), and John Clancy (from Indigo/Telecom Éireann). The very first meeting showed accounts where the profit and account registered a deficit of 206 Irish Pounds, and the current assets were deemed to be 220! (As Mr. Micawber would say, result: happiness.) David Mee, not on the initial directors list, was the first chairman; he was working for EUnet Ireland at the time.Alan Judge, now of Amazon, was a director from 1997-2004, and treasurer for the period 1997-2002 while it was still growing slowly. Indeed, he has a memory of how the company structure was decided: “It was a company limited by guarantee, which is the form that’s used for member organisations and charities, I think. With any other sort of structure there would have been shareholders and profit issues to be worried about. It meant there had to be a minimum number of members, if I recall correctly, for the annual reports and stuff. It also meant that the company articles had to have a vision for what would happen if you wrapped it up because there were no shareholders who you could give the surplus to. So I think it was effectively a charitable cause! Basically if it was ever wrapped up, the surplus would be donated to some cause related to the support of the internet in Ireland, or something like that, I can’t remember.”

Despite the occasional hiccup, the thing they’d built proceeded to run pretty stably for more or less the next six years, being taken care of out of people’s spare time. A time-honoured approach for Irish endeavours, it works up until the point that it doesn’t, but if the growth rate is small enough, you have enough time to react and make it professional before it’s too late. The INEX committee mailing list in the post-2000 timeframe has a number of mails from members bemoaning the fact that they can’t help out with various tasks due to day job pressures. Pressure was building to take the exchange to the next level, and the person who spear-headed the plan for the next level was Alex French,This is one of those rare cases where Alex and I not only eventually agreed about what to do, we also agreed at the time. who drew up the development plan in November 2002.

In one of the positive interactions between government and industry, making the INEX plan was actually partially motivated by the increasing amount of tech companies that the IDA were seeing queueing up, cap in hand, to avail of the wonderful opportunity of being located in Ireland. Many of those companies, in the 2000-2001 era, were concerned about the level of Internet connectivity that Ireland had: and in truth, we were, as an island, relatively poorly connected at that point.Although the government did make some progress in fixing that problem, by making a deal with a now defunct telco called Global Crossing to bring in a lot of fibre. What was worrying some of these prospects, however, was the question mark around the professionalism of the Internet Exchange of the country – for example, if it didn’t even have any staff, it was not at all clear to outside observers that it would be fit for purpose. So the plan states:

To fulfil a wider role as “Ireland’s IX”, INEX is enhancing its efforts to publicise and market its benefits to carriers, ISPs and hosting companies in Ireland and abroad. We will do this both directly and in a supporting role to development agencies such as the IDA, providing them with collateral and support to show that Ireland has a flourishing, member-led IX.

Building on its proven technical record and excellent industry relations, INEX is also committed to enhancing its management team and marketing position to provide the framework for a successful marketing and development effort.

Nick Hilliard and myself had been involved with INEX on a technical level in the early 2000s, after both Nick and myself went into consulting and contracting. So INEX was in good technical hands, as far as Nick’s involvement went anyway; we even managed to execute a quite hairy move of datacentres when the CARA contract expired and we moved all INEX equipment, lines, switches, and so on, to DEG’s otherwise mostly-disused facility out in the arse-end of north-west Dublin. Despite some members not moving their lines until the very last possible moment, we had proved that the exchange had the necessary technical depth to carry out whatever was required.Veterans of datacentre move projects will know what I mean.

But INEX needed something more.

No Barryers to growth

Now we come to the story of one of the most effective chief executives ever of an Irish Internet company – never mind tenure on its own, more or less any growth metric you could pick has been wildly successful for INEX during his stewardship, and all done on a part-time basis too! Barry Rhodes recalls the genesis of the round of INEX expansion that happened after that, and the beginning of his career in Ireland:

They decided that they needed someone full-time [at the end of 2003], which was when I interviewed and became General Manager. I’d joined EUNet Ireland in 1995. I think IEUNet itself started, I believe, in 1991, in Trinity. I’ve been in Ireland 39 years. I came here with Burroughs, which is now Unisys and then I was Sales Director with Business Automation, later renamed to BA Systems. I came to Dublin in ’77.

Barry had been in a fascinating array of roles before the INEX CEO one. Immediately before, he had been:

… four years in a software company. I was with this company, the Matrix Group. Have you heard of Computer Staff Recruitment? That was one of the companies within the Matrix Group. System Software, Keytrainer, Business Aautomation – which was the end I was in. We were the first people to sell IBM PCs. We imported them. Because of that, when the IBM PC came to Ireland, they made three organisations – Tomorrow’s World,I still bitterly resent Tomorrow’s World for messing up the repair of my Amstrad CPC. I remember crying in their offices in Dawson Street, as an embarrassed salesperson looked the other way. –niallm Datapac and Cara – were their first dealers. They “rapped us on the knuckles” for being a grey importer. Even though we were selling them, knew all about them, they didn’t give us the dealership for about six months or so. So we had to be good boys for six months. Then IBM gave it to us. We then became the biggest. We were the IBM Dealers of the Year two years running. We took on Compaq. Again, with Compaq, there were only Cara and ourselves. We used to sell them on to others. We were re-selling Compaqs.

The faint beginnings of Barry’s association with Internet systems really stems from around this time, when:

… we brought the first Unix systems in, which were Altos. I was a member, actually I don’t know – did I form it? – probably not, but I was an original member of the Irish Unix Users Association. People like John Carolan, Simon Kenyon. Simon was a great guy. He had this big, wooly, Aran sweater, which his wife had knitted. Around the bottom it said, “Unix is the trademark of Bell Laboratories.” I thought that was brilliant. Knitted into the bottom of the jumper!Echoing other commentary about governmental involvement in technical matters, it turned out that Barry was selling Altos against “a company called NorthStar Computers, which was down in Cork. They had a multi-user system, ie.: you could daisychain four systems together. It was outselling Altos, which was a true Unix system. There were two reasons. Obviously, the government wanted to support the Cork outfit. And the government in particular used to say, “Unix is a proprietary operating system and we don’t want to go proprietary.” Which was completely the wrong way round. They were buying NorthStars which were proprietary, and not in fact Unix.”.

Barry’s first meaningful experience with networking was setting up an EDI company after that experience. In Barry’s words:

EDI, electronic data interchange, was a precursor of the Internet, really. It was mainly for shipping companies, to try and smooth the flow of cargo, billing, and all that sort of thing. We took on – we, the Matrix Group – took on a guy who was ex-IBM and was set up in offices in Tooting in south London to sell EDI. He employed people. They all had big, fast cars, and so on. And we never got any revenue. It was always his dreams. It was our pension fund, you know, “This idea, this is the future. This is going to make you all millionaires!” and so on and so on.

Unfortunately, we had yet another repeat of the cashflow problems that plague so many companies, which in this case did indeed bring the company down.

I left the company. I had a lot of debt. I was still buying shares in the company, off another director who had left. I owned the building we were in – a seventh of it – seven of us directors had the building. But the rent was covering the interest until the company went into liquidation and suddenly we had no income coming in. My sole income from working was with the same company. When I saw the writing on the wall, I made myself redundant, left, and took these four years in the software company in the health area.

(Barry limits to himself to advising anyone who’s listening not to get involved in that particular technology area.)

When I left, Samir Naji phoned me and said, “I’d like to employ you as a consultant, for a day.” You know, generous rates for a day. I said ok. I went in there and he said, “Now I want to know everything that you did right in the company and everything you did wrong.”” And basically he just picked my brains as to all the good things and all the bad things and that was it. Paid me the cheque. And then he was gone.

As on so many other occasions, however, a fortuitous contact leads to something else unanticipated.

Three guys had started a company, Internet Services Ireland, and that was Tony Kilduff, Samir Naji, who became Horizon, and Paul Kenny, who is now chairman of Daft. He is with the Fallon Brothers there. Those three were the investors. They set up Internet Services Ireland, that then bought IEUNet, which had I think already changed its name to EUnet Ireland. EUnet Ireland was corporate-only. That’s what made it different from Barry and Colm’s Internet company, IOL. But when they bought it over they had a consumer product called HomeNet. So for a short while, there was this residential product on one side of the and corporate services on the other. The name disappeared very quickly, once it became EUnet Ireland. I got involved because they were looking for salespeople, Samir thought of me and asked if I’d be interested. And it was quite funny. Because David Mee [was really surprised] - Samir obviously hadn’t told him how old I was – it was 1996 so I was 53 at the time. David was expecting a much younger person to come in and I came through the door. He admitted this to me later, afterwards. He thought, “What are we doing here?! Internet, you know, nobody knows about the Internet! And here we’ve got this 50+ year old guy!”

While Barry had some peripheral exposure to the issues, equipment, financing, and so on, it is true to say that he didn’t really have Internet knowledge deep in his bones at that stage. But he and David Mee worked hard together, indeed learned together, and the company was grown very quickly. After a while the well-known Denis O’ Brien:

… presumably had been listening or reading and he had realised that a telecommunication company without an Internet company wasn’t really going to go anywhere. There was really nobody else around [to acquire]. There was Eircom, which was obviously tied to the incumbent. There was no other company. Indigo was there but Indigo’s suspect background made it an awkward acquisition target. So Denis saw that EUnet was the only option, and therefore he bought out Tony Kilduff, Paul Kenny, and Samir Naji and it was good deal for him. We were quite insistent that we kept a separate name. We wanted to keep EUnet Ireland but that was not going to happen. We took up Esat Net. There was Esat Telecom, although we didn’t really want to go there. Although, on reflection, maybe that was something that should have happened. But anyway, Denis was good enough to say that, “No, you can have your separate identity.” We had a separate office, so it was the same operation really, but under the Esat umbrella. That continued for a couple of years. We went out to Dundrum and we were in an office there and again, grew the business quite quickly. It wasn’t until BT came sniffing that they tried then, to integrate. I retired when BT took over Esat. But I carried on working as a consultant, training the telecoms people in internet services. So I was self-employed then. I did a few other things, but that was the main deal.

Unlike a number of other people, Barry seems to have had quite a succession of positive interactions with Denis:

In those days when it was smaller, he made a habit – everybody he recruited he met – usually for a breakfast meeting. It was a one-to-one in the early days and then it might be three together or there might be 10 or 12 at those meetings. I remember when he took us over, it was before Christmas and there was a Christmas party and he made a point of coming over and introducing and spending time with us. I wouldn’t say I ever knew him well, though Denis did take the trouble to give me credibility in a investment deal I was working on: to his eternal credit, when I walked in the door of his office, upstairs in Grand Canal Quay, he greeted me like a long-lost friend. Now he didn’t have to do that at all. He knew that it would help me with my dealing with my people if he gave me credibility. I thought that was good because he didn’t need to do it. Similarly for Lucy Gaffney. Now I didn’t get on with Lucy at all. But whenever I met her afterwards, she was always very friendly and always came over to say hello. Leslie Buckley, the same thing. They are ruthless. They tread on people. But behind it, there is good as well. They are nice people. In the end, you don’t want to get in the way of any of them!

So, to recap: from 1996 to 1997 Barry was in EUnet Ireland, from 1997 to 2001, it was Esat Net. Then he retired to be self employed and he was helping out sales folks. It was purely by chance that INEX swam into his ken:

A guy called Justin Verreccia was with BT; I met with him mostly when I was in and out of their offices. BT were members of INEX, one of the nine members at that time. When they were looking for somebody, it was only for two days a week, he mentioned my name there and it was Mike [Norris] and Denis [Curran] who were doing the interviews.

It suited Barry; he was “sort of” retired, but he didn’t actually want to, and did in fact need some income. Here was a job in a company strongly related to an industry he’d been working in, where he’d built up an extensive range of contacts, but the time commitment was certainly manageable: two days a week, which was where it stayed for about four years. When the development plan had been successfully executed, there were a lot more members, and it went to three days a week, and it’s currently still at that level.

However, although there was a considerable degree of matching background, as you can appreciate from the text above, there’s a good deal of specific expertise around Internet exchanges that needs to be acquired to be effective. Sadly, there were very few people who had it. What did Barry do?

I had to acquire it on the job. Obviously I was very lucky because Nick Hilliard was involved, as you were, in the early days. So I didn’t need to be technically proficient. I remember going to my first Euro-IX meeting and a lot of it was double-Dutch to me. […] My value, I think, to INEX, was having somebody who had the contacts, knew the industry in a general way and had the time to spend with both prospects and people like Department of Communications, IDA, and so on. And then I learned on the job, as they say. But I would have been… well, there was no need for me to be technically sound because I had Nick there, from the beginning.

It certainly suited Barry’s work style to acquire what was required by the simple expedient of talking to people:

I’ve always been able to talk with people at all levels. With some of our members you are dealing with the Chief Executive and with some of our members you are dealing with the network engineers. It’s a task where you have to be able to mix with all.

As someone who is an extrovert professionally, but an introvert personally, I appreciate greatly people who can switch between the two modes of talking, and make sense to both sides.

The Cluster Bombe

So we have a development plan. We have a technical team. We have a chief exec and a marketing officer (the redoubtable Eileen Gallagher, who joined in 2005 and can take considerable credit for expanding the exchange to the implausibly long list of names it has today.) That list is partially implausible because of the names, and partially because of the sheer length of the list: no-one, least of all me, anticipated the variety of organisations that we now see making their living at least partially or exclusively over the Internet. It was also not necessarily clear what that might mean for the Irish Internet exchange. Remember: Ireland is poor, depopulated, and on the periphery, right?

In fact there was a moment close to the beginning of Barry’s tenure when it looked like the exchange might well shrink, and continue to shrink, rather than grow:

When I started, there were only the 8 members and 2 of those left quite soon! One was AT&T and one was Cable and Wireless. So it was very much an ISP association after that, then content began to be important. INEX and I are lucky that this cluster [of content companies] began to appear.

But it was not a sure thing. As alluded to above, the IDA were receiving criticism about the Internet infrastructure, and had to have an answer for it, with deals like bringing Google into the country relying on the quality of the infrastructure, and in particular, having a credible Internet exchange. They initially looked to a commercial provider, PAIX:

I don’t know if you remember but there was another development through Robert Booth and Noel Meaney, who were in MetroMedia, now Citadel 200, they are EuroNetworks. They were running MetroMedia and they decided to do it the American way. Commercial data-centre offering peering. They went around to the banks, to everybody, you know, to whoever wanted it. It wasn’t just a question of doing it for ISPs and then later data content providers. They were going to try and put together a peering centre for anybody who wanted to exchange. There wasn’t room for two and INEX was already in existence. But for a time, the IDA thought [to themselves] maybe we should really go with PAIX. I don’t think they were too impressed with INEX at that stage, in that there wasn’t really a [commercial] infrastructure there. It was only one person from each member that used to meet as a committee, occasionally. That’s why me coming on board was fortuitous, because there was suddenly somebody they could talk to and somebody that could get involved in what we needed to expand and [assess] how much money we needed, and so on.

So it was accepted that the exchange needed to grow. They’d need a lot of money: this was a capital intensive business, and in order to connect a very large number of additional customers, that capital would need to go on more networking equipment. Not the kind you could get at the corner shop either, unless the corner shop happened to be cooled to a constant 23 degrees, and selling an appealing array of white noise. It was time to get a loan, and who better to get it from that the government, in the shape of the IDA, whose interests such an expansion definitely aligned with? INEX ended up borrowing about 650k EUR and spent it on a dramatic expansion of both speeds and capabilities. Ultimately it worked – today INEX has 81 actual traffic-exchanging members, and the IDA landed a large number of companies they probably wouldn’t have gotten otherwise – but there were aspects of the deal that could have been improved. Leaving aside the question of how much was spent on the IDA’s side making the deal happen,The IDA were worried about European law and didn’t want to help INEX in a way which would be against European regulations. the interest rate ended up being uncompetitive:

We were paying them 4% interest at a time when the interest rates were 2%! That’s why we paid it off as quickly as we could. There was a short period when 4% was good but for most of the time, that 4% - well, we could have done better on the open market.

Probably not a bank, however, seeing as how the exchange had run a deficit for a long time, and no particular credit history worth speaking of. However, the backing of the IDA (and implicitly the government) meant a lot. The actual support was not stellar, and others who have received (for example) Enterprise Ireland money will tell you that actually getting government money requires spending money (in terms of generating reports, research, and such like), sometimes more money than you actually end up getting. Barry feels that not that many opportunities were actually taken:

Part of the deal was “Oh yes, we want to introduce you. Anyone who has any interest in Ireland, we’ll introduce them to you.” It happened once, I think, that I can remember. That was the place in Athlone, Georgia Tech or something. I did two different presentations for them in Dublin and Eileen even went to America for them. We had to meet with Kevin (McCarthy) every few months or so, which was quite useful because he did have an idea of what was going on. I always felt that they got out of it what they wanted and the infrastructure did grow very quickly and therefore the Googles and the Yahoos and the Microsofts were happy enough.

Indeed, the progress was quite rapid essentially as soon as the infrastructure was put in place: as soon as INEX went into TeleCity, we got another swathe of members semi-immediately. But the most critical early prospect was Microsoft, whose name was capable of opening doors:

As soon as we went into TeleCity we got another 4 or 5 members because there were people in TeleCity that it made sense to join. But the biggest one was Microsoft. That’s what gave us the credibility. It was Declan Comerford in Microsoft who was really pro-getting a data centre here and he saw INEX as being part of that and so he pushed MS to consider it. Once they joined, that did give us a lot of credibility. And funnily enough, their traffic in the early days wasn’t very much. They were promising, “Oh yeah, we’re going to bring Hotmail over here”. But there wasn’t actually that much traffic, but having the name definitely helped.

An apparent first for INEX was getting Amazon to join. As an ex-Amazonian, I can tell you how reluctant they are to do things that don’t make financial sense, so they had balked at joining an exchange before, presumably on the basis that it wasn’t clear the upfront cost would be paid back by the ongoing cost savings.

Amazon hadn’t joined any internet exchange anywhere in the world but of course they set up here and we were dealing [primarily with] Alan Judge. He was the key figure, because he knew and was supportive. The funny thing about Amazon was that they were growing and they were growing quicker than they knew how to and so they didn’t even have things like a local legal team. TheyEileen Gallagher recalls it was Stephanie Burns. went through our Memorandum of Understanding, found something they wanted changed, we went to the AGM and changed one item in the MOU. That was huge for us, and it was nice in that at that time they hadn’t joined any other exchanges. It was a cluster effect afterwards. We got Yahoo, then Google.

The “national broadcaster” (how out of date those words seem today) started to get interested around then too:

RTE was another good one. They didn’t really understand how we could help them and the way we got them is that in Holland, [AMSIX[(http://ams-ix.net) got RTL, which is their national broadcaster. RTL had done a case-study and I got hold of this case-study saying how beneficial the exchange was to them. And then the BBC of course. Simon Lockhart, at one time he was saying 99% of their traffic was peered. So with those two, I then found the right person to go to, a guy called Marcus O’ Doherty, who has left RTE now. […] He didn’t know what I was talking about at the start but as soon as he saw the names of those two he thought, “Yeah this was something.” And they were beginning to understand that digital media was going to be important to them. And they joined and the traffic immediately started to go up. Initially it was just – I don’t think they had RTE Player – so it was just people listening to the radio stations. That was a big one for us.

Despite this frenetic growth, there were surprisingly few problems. There was never a problem with bad debt, or with members significantly disagreeing with the direction of the exchange overall. Part of that is obviously due to Barry and Eileen’s excellent (and dedicated) customer management, and part of it is that in contrast to other European exchanges, INEX has grown slowly and primarily been member-driven from day one. While other exchanges started off in their home country but have expanded abroad, INEX has only just recently expanded to Cork, which some people would regard as a separate country,Mostly Corkonians. but I’m a bit of a heretic and think of it as just another part of Ireland. Never having had the inclination to be hyper-ambitious or explicitly expansionist for the business - other than whatever the obvious next step was - we instead benefit from our willingness to help out at a European level:

We do really pull our weight there, we’ve been on different committees [in EURO-IX] and so on. Nick [Hilliard] is really highly thought of. Eileen was on the program committee and I was on the benchmarking committee, and so on. We are a small exchange, but we speak English and we know what we’re doing. […] When I was working for IMS and we working on these European projects, you’d have 8 people in a room, all speaking English but all coming from different native tongues. You didn’t know what had been agreed and what hadn’t. As soon as you saw it in writing you saw it had nothing to do with what the conversation was! So, yeah, I think that has helped us within the [wider European community].

At the end of the day, INEX is an association in the classic mould of early Internet entities. It doesn’t have to make a profit and indeed can’t, because it can’t be meaningfully distributed. Ultimately, it is there to help the members. As Barry says, “the biggest problem we have is how can we help an Eircom on one hand, and a small WISP on the other hand.” Another reason to focus on the members is because of that accident of geography we keep talking about:

Honestly there is no traffic that flows through Ireland. If you’re in some other country, Holland say, a lot of the traffic flows through Holland from Eastern Europe to Western Europe and to the States. Being in Ireland, there’s never going to be any traffic flowing through here. So we’re never going to grow as quickly, in terms of traffic. On the other hand, we have services for companies that some of the other European countries don’t have – like the content providers. […] I think we are well respected and that’s partly down to Nick and Barry and Eileen and myself – the four of us – but particularly the software we developed to run an exchange point – IXP manager, which has received esteem among the IXP technical people in Europe.

When you focus on members, you also get a chance to foster co-operation, to make the exchange a neutral meeting point where competitors can set aside difficulties:

One of the things that really surprised me, coming from a sales/commercial background, is how you could get competitors; competitors who are being encouraged to meet with each other. I go back to my Burrows days. It was Burrows and NCI, and if we were seen talking to a competitor, we’d be brought in in front of the management! That was until I went to Kenya. Those companies were the leaders in the market there but it was such a small community, the ex-patriate communities, you were members of the same clubs and things, that you realised you had to [lay aside differences]. You can still compete during the day and be friends and socialise at night. That was quite a surprise to me; that we could get consensus among people who compete strongly against each other. But also it’s in the nature of network engineers, who in particular have been good at this. If you had the chief executives of Eircom and BT and UPC or whatever, it probably wouldn’t be as easy to make it go. It’s because you are dealing with network engineers. They want to keep their networks running and they want to help make the Internet a better place.

By limiting its scope, INEX avoids a good deal of the political pressure that attends other Internet agencies in Ireland, such as the ISPAI. Barry admits to a certain amount of relief in not having Paul Durrant’s job.

We stick to being assisting people with exchanging traffic. We don’t have to get involved in any of the other issues; the ISPAI are involved in Net Neutrality, copyright, pornography and any of that. He’s welcome to that job. It does help to have that association as well.

The pressure is, people say “Why don’t you advertise more?” and we say, “What do we advertise?” Not advertise, but promote ourselves. We know who the prospects are and we try and talk to them. There’s nearly no point spending money trying to promote ourselves. We’re almost better trying to promote ourselves externally than we are internally. Outside of Ireland. So, we’re under the radar. Most people don’t know about us. Even in the IDA, most people wouldn’t know what we do, even though they’re talking to the network investment companies. In the Department of Communications there are one or two there who know, [and others] who wouldn’t have any sort of understanding. Does it matter? I don’t think so. As soon as we hear of people coming into Ireland that we think might be potential members, we contact them.

To my mind, INEX has inherited the mantle of technically focused, neutral, and member-oriented Internet service provision. Long may it continue.

An organisation in a rather different place is Eir.